Jason. R Jurjevich, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Practice, School of Geography, Development and Environment, University of Arizona

Nicholas Chun, Ph.D. Student, School of Geography, Development and Environment, University of Arizona

Individual confidentiality is protected in all U.S. Census Bureau (USCB) data products under current federal law. Recently however, innovations in computational science, combined with widely available sources of public data, are making it easier for outside parties to potentially identify individuals (Garfinkel et al. 2018; Jarmin 2018). It is now more difficult for the Bureau to provide quality statistical information while simultaneously safeguarding individual confidentiality (Abowd 2018). As a result, the Bureau has explored different techniques to uphold data privacy standards.

Beginning with 2020 Census data products, the USCB is implementing differential privacy to protect respondent confidentiality. In most simple terms, differential privacy distorts the data by injecting “noise” into publicly available data, making it more difficult to identify individuals. Differential privacy attempts to strike a balance between privacy and accuracy. This white paper addresses two questions: 1) how reliable are differentially-private data for Arizonans of color? 2) to what extent does differential privacy introduce unequal data distortion among Arizonans of color at sub-county geographies?

Differential privacy error is significant. It will almost certainly limit our ability to understand local neighborhood dynamics, make it more difficult to accurately measure disparate health and economic outcomes, and materially affect the Making Action Possible (MAP) data indicators. Our findings illustrate that less-accurate census data will almost certainly make it more difficult to achieve data-driven, equity-focused policy in Southern Arizona.

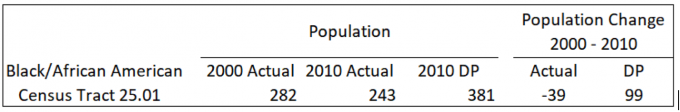

An example of the report’s findings are in Table 1 below. Differential privacy error will significantly affect the accuracy of 2020 Census data, especially for population subgroups, sub-county geographies, and less-populated areas. For example, consider the differential privacy error for the 2010 Black/African American population in Census Tract 25.01, located near the Santa Cruz River Park in South Tucson. The reported Census 2010 population is 243 individuals, compared to a differentially-private value of 381 This results in an absolute error of 138 individuals and a relative error of 57% (i.e., the relative error is more than half of the actual value). Put another way, the differential privacy error is so large that it masks the actual population decline of 39 Black/African American Tucsonans during 2000 to 2010; instead, differential privacy yields a population increase of 99 people.

Table 1. 2000 and 2010 (Actual and Differentially-Private) Black/African American Population, Census Tract 25.01

To read the full report visit the MAP Dashboard’s White Paper on the Effects of Differential Privacy.