Arizona Third Quarter Economic Outlook Update

30-Year Long-run Forecast Horizon

By George W. Hammond, Ph.D.

Director and Research Professor, EBRC

September 1, 2017

Arizona continues to add jobs, income, and residents at a faster pace than the nation. However, gains are coming at a slow pace compared to the state’s own history. Demographics (aging of the baby boom generation) is likely playing a role here, and this will continue to be an issue in the long run.

The 30-year forecast calls for Arizona to outpace the national rate of growth. However, that is not likely to be true for the state’s growth in per capita income. This is expected to remain positive and outpace inflation, but the state is not expected to beat the national rate. That means Arizona is forecast to lose ground to the nation on a key measure of prosperity.

During the past 40 years, Arizona has gradually fallen further and further behind the nation in per capita income, with slow wage growth contributing to the divergence. One key factor driving this has been the trend in four year college attainment, which has drifted from well above the national average in the 1940s to significantly below average today. If Arizona’s college attainment rate continues to lag behind the national average, it will be very difficult to close the income gap.

Arizona Recent Developments

Arizona’s job growth continued at a moderate pace in the second quarter of 2017. Over the year, the state added 54,200 jobs, which translated into 2.0% growth. That was slightly slower than the 2.1% rate posted in the first quarter, but above the national rate of 1.5%. The Phoenix metropolitan statistical area (MSA) added 50,300 jobs over the year in the second quarter, for 2.6% growth. The Tucson MSA added just 700 jobs over the year, for 0.2% growth.

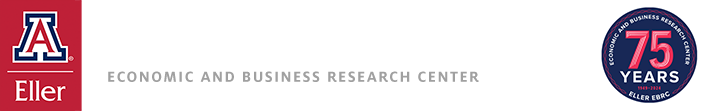

While job growth performance has not been particularly rapid so far this year, the buzz related to employment change has been unusually strong. The Economic and Business Research Center has been tracking firm announcements related to employment change since 1999. Exhibit 1 shows monthly announcements by firms related to both employment increase and employment decrease. This particular dataset tracks the number of announcements, not the number of jobs associated with the announcements. These announcements appeared in the major news outlets around the state, including the Arizona Republic, the Arizona Daily Star, among many others. Most of the announcements related to future expected employment changes at firms.

Exhibit 1: The Buzz About Arizona Employment Is Strong

Monthly Number of Firm Announcements Related to Job Increase or Decrease (Twelve Month Centered Moving Average)

While these announcements are related to future changes in published job data, the connection is loose. Nonetheless, our analysis of suggests that there is currently a lot more buzz about employment increase so far this year than in the past. For more on the characteristics of these data and for analysis of the trends for Phoenix and Tucson, see the Forecasting Project Directors Blog online at forecast.eller.arizona.edu.

According to preliminary data, Arizona’s personal income rose by 3.8% over the year in the first quarter of 2017, a bit above national growth of 3.1%. Gains in the first quarter reflected increases in net earnings from work (up 3.9%); dividends, interest, and rent (up 3.8%); and transfers (up 3.3%). The increase in net earnings from work was a bit disappointing, given that the state’s minimum wage increased substantially in January. Indeed, average wages per worker (calculated as total wage and salary disbursements divided by total nonfarm jobs) rose just 1.8% over the year. Keep in mind, however, that the preliminary wage and salary data are estimated based on nonfarm job growth and an econometrically-estimated “scale factor.” The revised data, available in September, will provide a better indication of the impact of the minimum wage increase on income, since wage and salary disbursements in that release will be based primarily on the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages.

Arizona Outlook in the Long Run

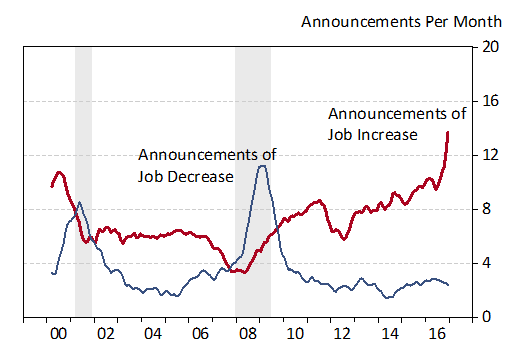

Exhibit 2 shows the long-run history and forecast for Arizona and U.S. job growth. The forecast calls for Arizona to add 1.6 million jobs during the 2017 to 2047 period, which translates into annual growth of 1.5% per year. That is well below the state’s average growth rate during the 30 years before the Great Recession and below the state’s average growth rate during the previous 30 years (1986-2016) of 2.4% per year. However, as the exhibit shows, Arizona is forecast to far outpace the national average rate of 0.7% per year. Slower growth for both Arizona and the U.S. is driven by a major demographic transition, as baby boomers retire in large numbers.

Exhibit 2: Job Growth Slows in the Long-Run for Both Arizona and the U.S.

Annual Growth Rates

Service-providing sectors account for most of Arizona’s job growth during the forecast. Indeed, education and health services; trade, transportation, and utilities; and professional and business services together account for 60.7% of total job gains during the next 30 years. The remaining service-providing industries together account for 35.3% of state job growth. Which leaves 4.0% for the goods-producing industries (mining, construction, manufacturing).

With solid, but slowing job growth during the next 30 years, Arizona’s population is projected to increase as well. The state is forecast to add 3.2 million new residents during the 2017-2047 period, for annual growth of 1.3% per year. That is a bit more than double the national rate of 0.6% per year. That growth is increasingly driven by net migration, as natural increase (the annual difference between births and deaths) decelerates due to the aging of the population.

Steady job gains translate into continued income growth, which is forecast to average 2.6% per year during the next 30 years, after adjustment for inflation. That outpaces the U.S., which is forecast to generate income growth averaging 2.0% per year after adjustment for inflation. Arizona’s income growth reflects gains across all three major sources: net earnings from work; dividends, interest, and rent; and transfers.

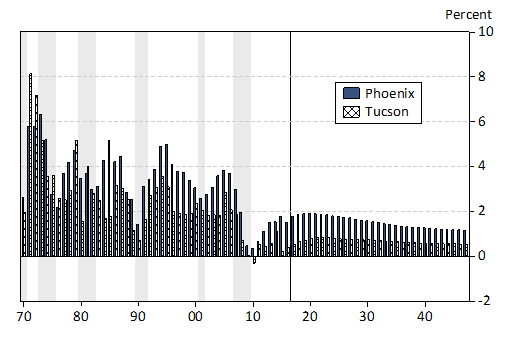

Both the Phoenix and Tucson MSAs are forecast to add jobs, population, residents, and income during the forecast. However, growth is expected to be much more rapid in Phoenix than in Tucson. Exhibit 3 shows population growth for Phoenix and Tucson during the next thirty years. Phoenix is expected to add 2.6 million new residents during the period, which translates into 1.5% growth per year. Tucson is forecast to add 227,000 residents, which translates into growth of 0.7% per year on average. Thus, growth in Phoenix is just over double the national pace, while Tucson’s growth is just slightly above the nation.

Exhibit 3: Population Growth in Phoenix Outpaces Tucson

Annual Growth Rates

Risks to the Outlook

In the long-run, the risks to the outlook revolve around the major drivers of economic development: labor force growth, productivity and innovation, investment in the physical capital stock, and human capital development.

Slowing labor force growth, driven by retirement of baby boomers, is already built into the baseline forecast. If growth turns out to be even slower, that will reduce state growth as well.

The national baseline forecast assumes that productivity growth rebounds from the weak performance of recent years. If that fails to materialize, look for slower than expected gains nationally and in Arizona.

Investment in the private physical capital stock is expected to slow during the forecast, but if growth turns out to slow more than expected, it will reduce overall economic performance. In addition, remember that infrastructure (highways, roads, water, sewer, airports, border ports, rail, telecommunications) matters as well.

Human capital (typically measured by educational attainment) will continue to matter. For Arizona, this is particularly important, because the state already lags well behind the nation. If Arizona’s education gap rises during the next 30 years, it will set the stage for ever larger income gaps with the U.S.

Finally, water remains a concern for the long run. Shortages in the West have the potential to drive up residential and business costs and restrict growth.

Forecast data for Arizona, Phoenix MSA, and Tucson MSA.

Need to know more?

Contact George Hammond about the benefits of becoming a Forecasting Project sponsor!