Alberta H. Charney, Ph.D., Senior Research Economist

June 5, 2014

Contents:

Introduction

A Deceiving Trend in Total Nominal Taxable Sales

Sales Tax Base is Behaving Differently than Personal Income

Components of Sales Tax Categories as a Share of Personal Income

National Data Reveals Similar but Smaller Trends

Online Purchases

Aging of Population

Labor Force Participation Rate

Income Distribution

Consumer Debt and Student Debt

Conclusions

End Notes

Introduction

Arizona governments rely heavily on the sales tax, a.k.a. the transaction privilege tax, at both the state and local levels. The State and cities/towns are empowered to impose sales taxes. In addition, counties and incorporated cities/towns receive a portion of the sales taxes collected by the state in the form of state-shared sales taxes. Sales tax collections retained by the state, after sharing with counties and cities/towns, was approximately $3.6B in 2012, [i], or approximately 48-49% of total tax revenues to the General Fund. [ii]

There are some troubling long-term trends in the sales tax base, trends that have substantially worsened since 2005. Although total taxable sales continue to grow, the taxable sales tax base is a diminishing share of personal income. In just a little over 20 years, the total sales tax base as a share of personal income has fallen from 60 percent to slightly over 40 percent. This is a one-third reduction in the taxing capacity of the sales tax in just a little over two decades. This article will discuss the trends in Arizona’s sales tax base and suggest some potential causes.

A Deceiving Trend in Total Nominal Taxable Sales

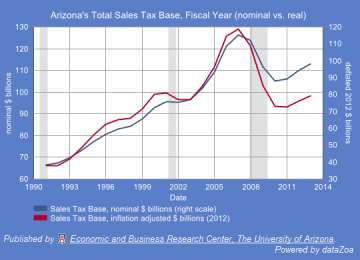

The total nominal sales tax base is growing. The blue line (right scale) Figure 1 displays the sum of nominal total taxable sales in Arizona. For two reasons, this pattern differs somewhat from the pattern of total sales tax revenues. First, tax rates have changed over time and second, there are some differences in the tax rates imposed across the 15 or so categories of sales taxes in the state. The variable shown in the graph and identified as total taxable sales is the sum across all the taxable categories of sales. Examining this graph, the total sales tax base grew from approximately $38B in FY1991 to approximately $98B in FY2013, an increase of 250% over the time period. Sales taxes mushroomed during the period of the housing bubble, reaching a peak of $115B in FY2007 before the Great Recession. Nominal taxable sales have rebounded by approximately 12% since the bottom of the trough (FY2010), and this chart leaves the impression that the sales tax base may be back on the pre-bubble FY1991-FY2002 growth trend. [iii]

Figure 1. Arizona’s Total Sales Tax Base ($Bil), Fiscal Year

Although there has been some growth in deflated taxable sales since the bottom (approximately 5.5%), deflated taxable sales are well below where they should be, based on past trends.

However, deflating the data series to remove the effects of inflation on the series shows a very different result. The red line (left scale) in Figure 1 was divided by the Consumer Price Index for Urban Dwellers in the Western Region (adjusted to equal 1.0 in 2012). This division creates a real, or deflated, series in 2012 constant dollars. It is becomes very clear from the red line that inflation adjusted taxable sales are not even close to the pre-bubble 1991-2002 trend line. The deflated sales tax base in FY2010 was similar to its FY1999 level. Although there has been some growth in deflated taxable sales since the bottom (approximately 5.5%), deflated taxable sales are well below where they should be, based on past trends.

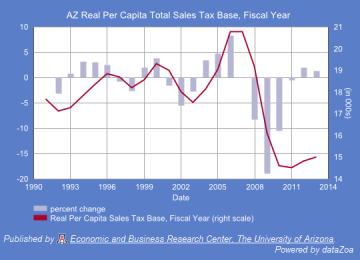

The tax base trend is even worse when total taxable sales are both deflated and divided by population. The resulting per capita sales tax base (Figure 2) fell more than 30% between the peak of the housing bubble in FY2007 and the low point in FY2011. The FY2013 level is almost 18% below the average of the FY1991-FY2002 period prior to the housing bubble and the Great Recession. This means that, on a per capita basis, the sales tax base has 18% less purchasing power to provide government services to the current population than before the bubble.

Figure 2. Arizona’s Real Per Capita Total Sales Tax Base (Deflated, 2012 Dollars), Fiscal Year – on a per capita basis, the sales tax base has 18% less purchasing power to provide government services to the current population than before the bubble.

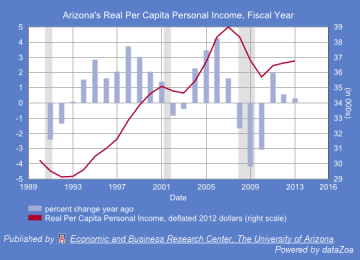

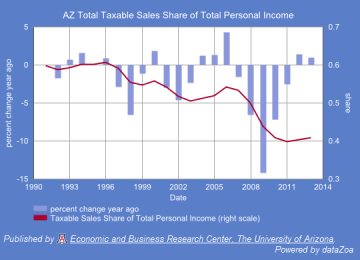

Sales Tax Base is Behaving Differently than Personal Income

Figure 3 shows the deflated per capita personal income in Arizona over the same time period as Figure 2. In this graph, Arizona’s personal income is divided by the same deflator used for deflating the total sales tax base and by the same population numbers. Clearly the trends in real per capita personal income do not account for the extreme decline in real (deflated) total taxable sales per capita shown in Figure 2. Real per capita personal income fell by only 8.4% from the peak in 2007 to the trough in FY2010, which is a much smaller decline than the 30% fall in real per capita taxable sales over the same time period. Unlike the 2013 real per capita sales tax base, which was 18% below the FY1991-FY2002 average, real per capita income in 2013 is 15.5% above its average in the earlier time period. Therefore, only a small portion of the decline in real per capita taxable sales can be attributable to a change in real per capita income.

As shown in Figure 4, an important trend affecting real per capita taxable sales is that a smaller and smaller share of each dollar of income is being spent on taxable items. In the early 1990s, almost 60% of Arizona’s personal income was spent on taxable items but that share is currently around 40%, representing a fall of more than 33% in just a little over two decades. This decline the share of income spent on taxable items can be thought of as a reduction in the taxing capacity of the Arizona sales tax and it is unclear how much further this share will fall. The rest of this article will examine some possible reasons for this decline and try to determine if or when taxable sales as a share of personal income will stabilize or begin to increase again.

Components of Sales Tax Categories as a Share of Personal Income

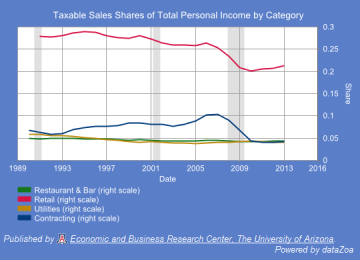

An important question in understanding whether the dramatic reduction in the taxable sales to income ratio is due to a particular component of total taxable sales or do most/all components exhibit the same pattern? Of the four largest components of taxable sales, three of them are declining as a share of income: retail, restaurant and bar sales, and utilities. Contracting sales, in contrast, has a unique pattern but fell dramatically as a share of income in recent years.

Retail sales, as a share of personal income, fell from approximately 29% in FY1990 to a low of 20% in FY2010 (Figure 5). It increased slightly to 21% from FY2010 to FY2013, a very small change. Restaurant and bar taxable sales were just under 4.9% of total personal income in 1990 but fell to 4.1% in FY2009. Although the restaurant and bar sales category has rebounded some, its FY2013 share of income (4.4%) is still well below what it was in FY1990. Utility sales in Arizona in FY1990 were 5.8% of total personal income but they represented only 4.1% in 2013, a substantial decline.

Figure 5: Arizona Taxable Sales as a Share of Personal Income, Fiscal Year, by Category: Restaurant and Bar Sales, Retail, Utilities, Contracting.

Contracting taxable sales, as a share of personal income, shows a very different pattern than the other three categories. Contracting grew as a share of personal income from 6.7% in FY1990 to 10.7% at the peak in FY2007. Since then, the ratio of contracting taxable sales to personal income has declined by 62% and has been hovering in the 4.0-4.2% range during the last three years (FY2011-FY2013). Although contracting as a share of income has not been steadily declining since FY1990, the rapid fall of since 2007 has substantially contributed to the steep slope since FY2007 shown in the total taxable sales to income ratio in Figure 4.

National Data Reveals Similar but Smaller Trends

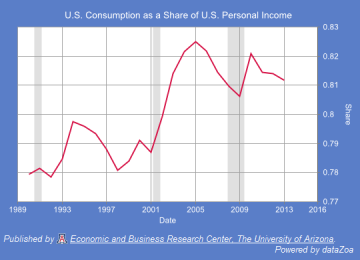

When examining Arizona’s trend in taxable sales relative to income, the obvious question is whether Arizona is unique or whether this is happening nation-wide. A second related question is whether total consumption is declining as a share of personal income or whether it is just the items that are taxable under the sales tax in Arizona.

An examination of total U.S. consumption relative to U.S. personal income shows that, over time, consumption has risen relative to income throughout the FY1990-FY2013 period, although there have been some major fluctuations over that period (Figure 6). The housing bubble can be seen clearly during the steep rise in the consumption to income ratio from FY2002 through FY2005, when more than 82% of all income was spent on consumption. Although there was a substantial decline from FY2005 through FY2009, the overall trend has continued to climb.

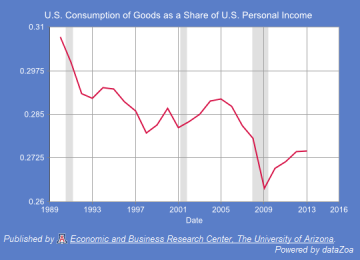

Not all consumption in Arizona is taxable. In general, goods are taxable and services are not, although there are a few exceptions to this rule, e.g., food for home consumption in Arizona is not taxable. U.S. consumption of goods relative to U.S. personal income is a somewhat closer national representation of items that comprise Arizona’s tax structure (Figure 7). The data show that the consumption of goods, relative to personal income, is also declining nation-wide. Consumption of goods as a share of personal income fell from 30.7% to 27.4%, a decline of 11%. While substantial, this decline in no way compares to the 33% decline shown in Arizona’s tax base relative to income over the same period.

Online Purchases

There are several possible explanations for why Arizona’s share of income spent on taxable items has been eroding over time. One is the existence of online sales that diminish the sales of in‐state brick and mortar businesses. Online sales are taxable if those purchases are from entities that have a legal nexus in the state. Specifically, online purchases from stores like Best Buy, Home Depot, and Macy’s would all be taxed as though those purchases were made locally in the stores. However, online purchases from strictly out ‐of‐state businesses, e.g., LLBean, Zappos.com, would not be charged state or local sales taxes.

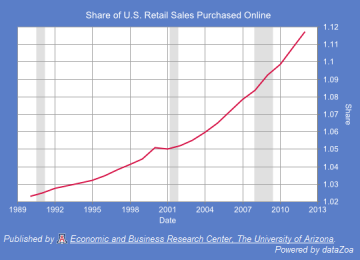

To examine the potential loss in taxable sales due to online purchases, a national “retail” sales figure was constructed to resemble the tax base used here in Arizona. It was created by using national retail sales data, excluding gasoline sales and food for home consumption. As defined, it includes retail sales made online. This retail sales series was divided by the same series, excluding online sales. Figure 8 shows the ratio of total retail sales (including online sales) to retail sales (excluding online sales) in the U.S. This historical data series only went back to 1992 so data prior to 1992 were estimated simply by extending the series back a few years with a trend. From this graph, national online sales are an increasing share of total “retail” sales and currently represent 12 percent of the total.

Figure 8. Share of U.S. Retail Sales (Defined Similarly to Arizona’s Taxable Category) Purchased Online

In 1990, online (or mail-order) purchases were only 2% of retail sales (defined similarly to Arizona’s retail taxable category) and currently represent closer to 12% of all purchases. Does this mean that online sales account for almost a third of the 33% decline in total taxable sales relative to personal income? No, because retail sales, as defined in Arizona, represents slightly more than half of all taxable sales in the state (about 52% in 2013). Therefore, online sales could account for at most 5 of the total 33 percentage point decline. But even that significantly overstates the scale of the tax-free online sales because any online purchase made from stores that have a physical presence in the state (aka legal nexus) will have taxes applied. So, although online and mail-order sales has an effect on Arizona’s sales tax base, it probably accounts for only a few percentage points of the total 33% decline in taxable sales relative to personal income.

Aging of Population

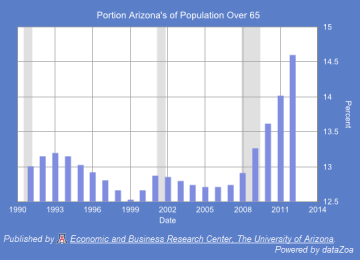

The portion of population over 65 was 13% of the population in 1990 (Figure 9). Although the portion over 65 varied over time, it stayed below 13% until 2008. In just the few years between 2008 and 2012, the portion increased to 14.6% and this portion is expected to continue to increase as the post WWII baby boom generation continues move into their mid-60s.

The aging of the population means that spending patterns are likely to change. Seniors tend to buy more services than younger people. Specifically, persons over 65 spend 12.7 percent of their income on healthcare (includes health insurance, medical services, drugs and medical equipment), all of which is non-taxable. This share of income spent on healthcare is much higher than the 6.9% of income spent on healthcare, averaged across all age groups. Seniors spend relatively higher shares of their income on property taxes, maintenance and repair (of dwelling), and insurance. Again, these are not taxable under the sales tax. Similarly, several other categories of expenditures, which are taxable, decrease with the age of the consumer, e.g., apparel, vehicles, and restaurant and bar purchases. [iv]

Labor Force Participation Rate

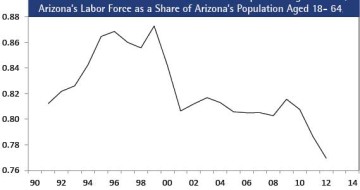

Arizona’s labor force participation rate has been falling since FY1999 (Figure 10), with major declines during the early 2000 recession and again during the recent recovery (since FY2009). The labor force participation rate is defined as the labor force divided by the population most likely to be working, i.e., population aged 18 through 64. Therefore, this graph is independent of the

increasing share of population over 65 and the population under 18. The labor force, in turn, is defined as the total number of people who are either working or actively looking for work. This decline in Arizona’s labor force, as a share of the population aged 18-64, is troubling. From a peak of 87% in FY1999, the share of Arizona population aged 18-64 in the labor force has fallen to 77% in FY2012.

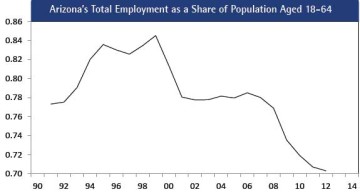

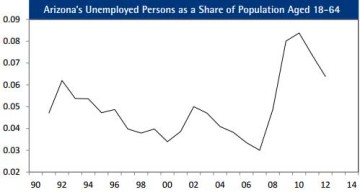

Is this decline due to a reduction in jobs relative to that age group or to fewer people actively looking for work? Figure 11 is a graph of total employees in Arizona as a share of population aged 18-64 and Figure 12 is a graph of unemployed persons as a share of the population aged 18-64. Unemployed persons are, by definition, in the labor market and must be actively seeking employment. From these two graphs, it is clear that the recent decline in the labor force (as a share of population aged 18-64) is not due to fewer persons looking for jobs. The share of the population aged 18-64 looking for jobs is more than double what it was prior to the recession that began December 2007. It increased by 5% from FY2006 to FY2010 and then fell off by a little more than 1.5% since then. The decline in the labor force participation rate is due predominantly to the recent steep decline in employment, relative to the 18-64 population.

When fewer people of working age have jobs, overall household spending patterns have to change. Households have to cut back on many of the extras and that is likely to include many of those items that are taxable in the state of Arizona.

Income Distribution

According to Piketty and Saez, income has become much more concentrated throughout the U.S., particularly since 1975. From 1975 to 2007, the share of income captured by the top 1% climbed from 8% to almost 23%.[v] In a recent report by the Economic Policy Institute, income inequality was examined for each state and the District of Colombia.[vi] In Arizona, between 1974 and 2007, total income grew by 17%, but 84% of all that income growth accrued to the top 1%. Arizona’s income distribution worsened even further during the 2009-2011 recovery years. During this time period, total Arizona income increased only by 0.1%. During this same time period, the income of the top 1% grew by 5.9% while the income of the bottom 99%’s declined by 1.0%. Therefore, the share of total growth of income captured by the top 1% over these years was 686%.[vii]

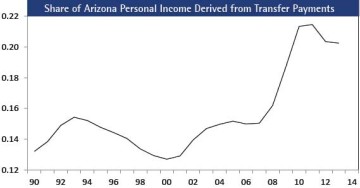

There is no precise measure of income distribution or income concentration in Arizona that can be graphed over time since 1990. However, there are two measures that are correlated with how income is distributed. First is the share of income that is represented by transfer payments. Transfer payments are growing, partly because the population is getting older and a higher share is receiving social security payments. In addition, when wages stagnate and the jobs situation is weak, a higher percentage of people receive other forms of government transfers, including food stamps and unemployment insurance. Figure 13 shows of the portion of personal income that is transfer payments. This has risen from approximately 14 percent in 1990 to approximately 21 percent in 2011 and most of that increase occurred since 2007. Transfer payments are predominantly either temporary safety net support for persons who are unemployed or earning below the poverty line or they are social security payments made to retirees, the so-called “fixed-income,” as it has often been characterized. People receiving these types of payments are either in financial stress or are retired and they tend to spend less than they would otherwise.

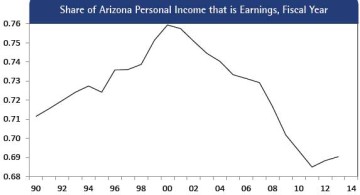

Another measure that is related to the income distribution is the share of income going to workers via wages and salaries. The fact that wages have stagnated and the labor share of income is declining is an associated characteristic of the increasingly concentrated income distribution. Figure 14 shows the share of personal income that is attributable to wages and salaries. Wages and salaries as a share of personal income rose from 71% to 76% of personal income between FY1990 and FY2000. Since then, the share of personal income attributable to earnings has fallen to 69%. Although the decline in this share was not as precipitous as the decline in taxable sales relative to personal income, the 10 percent decline in the share of income can have a substantial effect on overall spending.

Consumer Debt and Student Debt

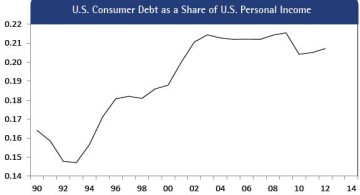

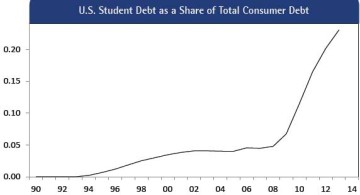

Consumer debt has grown since 1990, increasing from 16% of U.S. personal income in 1990 to over 21% (Figure 18). Consumer debt stayed above 21% of personal income from 2002 through 2009 and then fell to approximately 20.5% during the next three years. When consumer debt is this high, it crowds out new purchases because consumers have to make substantial payments to service their debt.

A major change in recent years is the dramatic increase in student debt, which has become a major component of total consumer debt. This can have an adverse effect on spending on taxable items that is separate from the level of total consumer debt. Historically, young people, upon graduating from college, formed households and bought homes, furnishings and appliances. Student debt, as a share of total consumer debt, has mushroomed from virtually nothing in 1990 to over 23% of all consumer debt in 2012 (Figure 21). Although the younger age groups want to spend and establish themselves in separate households, they can’t because they are saddled with enormous educational loans.

Conclusions

Trends that may be affecting the ratio of Arizona’s taxable sales to personal income have been identified in this article. It’s impossible to attribute the entire decline in this ratio to any one of these trends or even to a combination of them. But what is clear is that the capacity of the sales tax in Arizona has been shrinking over time and it will become more and more difficult to raise state and local revenues from this tax.

For decades, most economic and forecasting models related local economic activities (as opposed to export-base activities that sell goods and services out of state) to personal income. But over time, the relationship between the sales tax base and personal income has substantially changed. It may not be just the level of personal income that is important in explaining taxable sales, it is also the source of income and, indirectly, how income is distributed across the population. In addition, the relationship between taxable sales and personal income may be related to demographics and the spending patterns of different age groups, seniors in particular. High consumer debt and the increasing share of total consumer debt that is student debt dampens the spending of those who should be establishing new households and buying and furnishing homes.

Of particular concern for the future of the sales tax and its ability to produce revenues in Arizona is that all of the trends identified in this article are expected to continue. The share of population over 65 is expected to continue to grow as the baby boomers continue to move into that age group. Income is expected to continue to concentrate as most income growth is expected to accrue to the top 1% and earnings as a share of income is expected to continue to fall. Consumer debt is expected to stay at its current relatively high level and student debt as a share of consumer debt is expected to continue to rise. There has been some movement toward taxing online sales, but the tax-related playing field between online sellers and local brick and mortar sellers still strongly favors the online sellers. Although there must be some lower limit for the taxable sales: personal income ratio, it is impossible to determine what that limit is.

End Notes:

[i] Joint Legislative Budget Committee’s 2012 Handbook, available on their website: http://www.azleg.gov/jlbc/12taxbook/12taxbk.pdf

[ii] This percentage of the General Fund tax revenue was computed by dividing Sales and Use Tax collections by (Total General Fund Tax Revenues less Revenues from the Temporary Tax) for the Fiscal Year 2013. Temporary sales tax revenues were subtracted from the total because 2013 was the last year of those revenues. Data obtained from the Joint Legislative Budget Committee’s website: http://www.azleg.gov/jlbc/historicalgeneralfundrevenuecollections.pdf [iii] It should be noted that food for home consumption is not included in this total because it was exempted from the sales tax in the early 1980s. [iv] Consumer Expenditure Survey, by age group, http://www.bls.gov/cex/2012/combined/age.pdf [v] Figures read off a chart by Piketty and Saez, posted in the Economic Policy Institute’s report “The Increasingly Unequal States of America; Income Inequality by State, 1917 – 2011,” accessed 5/13/2014 at http://www.epi.org/publication/unequal-states/ [vi] Ibid, Table 1. [vii] Ibid, Table 2.Photo of puzzle hundred dollar bill with pieces near by courtesy of Shutterstock.